Victims of a desperate event, a child (left) and baby llama (right) were part of the sacrificial killing of more than 140 children and over 200 llamas on the north coast of Peru around A.D. 1450.

More than 140 children were ritually killed in a single event in Peru more than 500 years ago. What could possibly have been the reason?

EVIDENCE FOR THE largest single incident of mass child sacrifice in the Americas— and likely in world history—has been discovered on Peru's northern coast, archaeologists tell National Geographic.

More than 140 children and 200 young llamas appear to have been ritually sacrificed in an event that took place some 550 years ago on a wind-swept bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, in the shadow of what was then the sprawling capital of the Chimú Empire.

Scientific investigations by the international, interdisciplinary team, led by Gabriel Prieto of the Universidad Nacional de Trujillo and John Verano of Tulane University, are ongoing. The work is supported by grants from the National Geographic Society.

While incidents of human sacrifice among the Aztec, Maya, and Inca have been recorded in colonial-era Spanish chronicles and documented in modern scientific excavations, the discovery of a large-scale child sacrifice event in the little-known pre-Columbian Chimú civilization is unprecedented in the Americas—if not in the entire world.

Preserved in dry sand for more than 500 years, more than a dozen children were revealed over the course of a day by archaeologists. The majority of the ritual victims were between eight and 12 years

"I, for one, never expected it," says Verano, a physical anthropologist who has worked in the region for more than three decades. "And I don't think anyone else would have, either."

The researchers are in the process of submitting a report on scientific results of the discovery to a peer-reviewed, scientific journal.

A Stunning Tally, and a Tragic End

The sacrifice site, formally known as Huanchaquito-Las Llamas, is located on a low bluff just a thousand feet from the sea, amid a growing spread of cinderblock residential compounds in Peru's northern Huanchaco district. Less than half a mile to the east of the site is the UNESCO World Heritage site of Chan Chan, the ancient Chimú administrative center, and beyond its walls, the modern provincial capital of Trujillo.

See massive ancient drawings discovered in the Peruvian desert.

At its peak, the Chimú Empire controlled a 600-mile-long territory along the Pacific coast and interior valleys from the modern Peru-Ecuador border to Lima.

Once one of the largest cities in the Americas, Chan Chan was the capital city of the ancient Chimú civilization. How long ago did the Chimú people live, and what brought about the fall of their civilization?

Only the Inca commanded a larger empire than the Chimú in pre-Columbian South America, and superior Inca forces put an end to the Chimú Empire around A.D. 1475.

Guadalupe

Pacasmayo

Paiján

Cartavio

PERU

TRUJILLO

SOUTH

AMERICA

Huanchaquito

AREA

ENLARGED

Chan Chan

SOREN WALLJASPER, NG STAFF

Human settlements along Peru's north coast are susceptible to climactic disruptions caused by El Niño weather cycles.

PACIFIC

OCEAN

A satellite image shows the proximity of the Huanchaquito-Las Llamas sacrificial site to the sprawling ruins of the ancient Chimú capital of Chan Chan.

Huanchaquito-Las Llamas (generally referred to by the researchers as "Las Llamas,") first made headlines in 2011, when the remains of 42 children and 76 llamas were found during an emergency dig directed by study co-author Prieto. An archaeologist and Huanchaco native, Prieto was excavating a 3,500-year-old temple down the road from the sacrifice site when local residents first alerted him to human remains eroding from nearby coastal dunes.

By the time excavations concluded at Las Llamas in 2016, more than 140 sets of child remains and 200 juvenile llamas had been discovered at the site; rope and textiles found in the burials are radiocarbon dated to between 1400 and 1450.

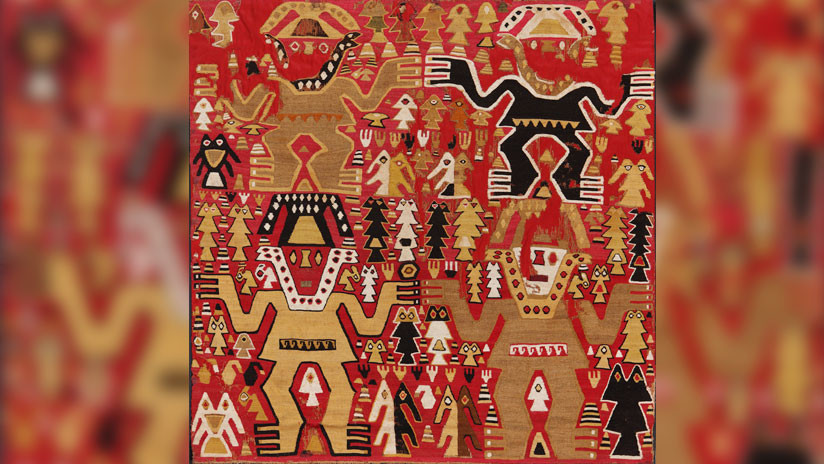

Many of the children had their faces smeared with a red cinnabar-based pigment during the ceremony before their chests were cut open, most likely to remove their hearts. The sacrificial llamas

Evidence for the ritual killings includes a skull stained with red cinnabar-based pigment, a human rib bone with cut marks, and a sternum severed in half.

The skeletal remains of both children and animals show evidence of cuts to the sternum as well as rib dislocations, which suggest that the victims' chests were cut open and pulled apart, perhaps to facilitate the removal of the heart.

The remains of three adults—a man and two women—were found in close proximity of the children and animals. Signs of blunt-force trauma to the head and a lack of grave goods with the adult bodies lead researchers to suspect that they may have played a role in the sacrifice event and were dispatched shortly thereafter.

The 140 sacrificed children ranged in age from about five to 14, with the majority between the ages of eight and 12; most were buried facing west, out to the sea. The llamas were less than 18 months old and generally interred facing east, toward the high peaks of the Andes.

Archaeologist Gabriel Prieto, second from left, excavates the coastal lot where the ritual event took place more than 500 years ago. He trains local students to become the next generation of scientis. Kit

A Scatter of Footprints, Frozen in Time

The investigators believe all of the human and animal victims were ritually killed in a single event, based on evidence from a dried mud layer found in the eastern, least disturbed part of the 7,500-square-foot site. They believe the mud layer once covered the entire sandy dune where the ritual took place, and it was disturbed during the preparation of the burial pits and the subsequent sacrifice event.

Archaeologists discovered the footprints of sandaled adults, dogs, barefoot children, and young llamas preserved in the mud layer, with deep skid marks illustrating where reluctant four-legged offerings may have been forcibly coaxed to their end.

An analysis of the footprints may also enable the archaeologists to reconstruct the ritual procession: It appears that a group of children and llamas was led to the site from the north and the south edges of the bluff, meeting in the center of the site, where they would have been sacrificed and buried. The bodies of a few children and animals were simply left in the wet mud.

Local residents alerted archaeologist Gabriel Prieto to the sacrificial site in 2011, noting that human bones were eroding from the dunes around their homes.

Many of the 200 sacrificial llamas are so well preserved that after 500 years, researchers could recover the ropes they were bound with, stomach contents, and plant remains caught in their fur.

Many children show evidence of having their faces smeared with red pigment before death. DNA analysis indicates that both boys and girls were sacrificed.

A young llama (left) and shrouded child were buried in the same pit—a common phenomenon at Las Llamas, but a generally unusual find in the pre-Columbian Andes.

A child seems to hold a hand in its mouth as the remains of a llama curl around its skull.

Many of the cotton shrouds that wrapped the victims are well preserved. They have been carbon dated to between A.D. 1400 and 1450.

Both children and llamas were brought to the coast from far-flung corners of the Chimú Empire to be sacrificed, according to preliminary isotopic studies and analysis of skull modification.

An Unprecedented Event?

If the archaeologists' conclusion is correct, Huanchaquito-Las Llamas may be compelling scientific evidence for the largest single mass child sacrifice event known in world history.

Until now, the largest mass child sacrifice event for which we have physical evidence is the ritual murder and interment of 42 children at Templo Mayor in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán (modern-day Mexico City).

The discovery of individual child sacrifice victims recovered from Inca mountaintop rituals has also captured the world's attention.

Outside of the Americas, archaeologists at sites such as the ancient Phoenician city of Carthage debate whether child remains found there constitute ritual sacrifice and, if so, if such ritual events took place over the course of decades or even centuries.

Verano emphasizes that such clear-cut evidence for deliberate, singular mass sacrificial events such as those evidenced at Las Llamas, however, is extremely rare to find in archaeological contexts.

Analysis of the remains from Las Llamas shows that both children and llamas were killed with consistent, efficient, transverse cuts across the sternum. A lack of hesitant ("false start") cuts indicates that they were made by one or more trained hands.

"It is ritual killing, and it's very systematic. Lo

National Geographic grantees Gabriel Prieto, left, and John Verano, right, have spent several seasons excavating the sacrificial site of Las Llamas.

Human sacrifice has been practiced in nearly all corners of the globe at various times, and scientists believe that the ritual may have played an important role in the development of complex societies through social stratification and control of populations by elite social classes.

Most societal models that look at human sacrifice, however, are based on the ritual killing of adults, says Joseph Watts, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

"I think it's definitely harder to explain child sacrifice," he says, then pauses.

"Also, at a personal level."

Negotiation With Supernatural Forces

The mass sacrifice of only children and young llamas that took place at Las Llamas, however, appears to be a phenomenon previously unknown in the archaeological record, and it immediately raises the question: What would motivate the Chimú to commit such an act?

El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a climate pattern that warms and cools the tropical Pacific Ocean. During an El Niño warm phase, surface temperatures (in red) stretch across the equator.

Prieto concedes that this is often the first question he encounters when he shares his research at Las Llamas with scientific colleagues and the local community.

"When people hear about what happened and the scale of it, the first thing they always ask is why."

The layer of mud found during excavations may provide a clue, say the researchers, who suggest it was the result of severe rain and flooding on the generally arid coastline, and probably associated with a climate event related to El niño.

Elevated sea temperatures characteristic of El Niño would have disrupted marine fisheries in the area, while coastal flooding could have overwhelmed the Chimú's extensive infrastructure of agricultural canals.

The Chimú succumbed to the Inca only decades after the sacrifices at Las Llamas.

Haagen Klaus, a professor of anthropology at George Mason University, has excavated some of the earliest evidence for child sacrifice in the region, at the 10th- to 12th-century site of Cerro Cerillos in the Lambayeque Valley, north of Huanchaco. The bioarchaeologist, who is not a member of the Las Llamas project, suggests that societies along the northern Peruvian coast may have turned to the sacrifice of children when the sacrifice of adults wasn't enough to fend off the repeated disruptions wrought by El Niño.

"People sacrifice that which is of most and greatest value to them," he explains. "They may have seen that [adult sacrifice] was ineffective. The rains kept coming. Maybe there was a need for a new type of sacrificial victim."

Researchers continue to unravel the events at Las Llamas, and they hope to eventually explain why and how humans appealed to the supernatural in an attempt to control an unpredictable natural world.

"It's impossible to know without a time machine," Klaus says, adding that the Las Llamas discovery is important in that it adds to our knowledge about ritual violence and variations on human sacrifice in the Andes.

"There's this idea that ritual killing is contractual, that it's performed to get something from supernatural deities. But it's actually a much more complicated attempt at negotiation with those supernatural forces and their manipulation by the living."

Future Histories for Past Victims

The scientific team investigating the Las Llamas sacrifices is now undertaking the painstaking work of unraveling the life histories of the victims—such as who they were and where they may have come from.

Although it is difficult to determine sex based on skeletal remains at such a young age, preliminary DNA analysis indicates that both boys and girls were victims, and isotopic analysis indicates that they were not all drawn from local populations but likely came from different ethnic groups and regions of the Chimú Empire.

Evidence for cranial modification, practiced in some highland areas at the time, also supports the idea that children were brought to the coast from farther-flung areas of Chimú influence.

Since the discovery at Las Llamas, the research team has discovered archaeological evidence around Huanchaco for similar, contemporaneous mass child-llama sacrifice sites, which are the subject of ongoing scientific investigation with the support of the National Geographic Society.

"Las Llamas is already such a unique site in the world, and it makes you wonder how many other sites like this there may be out there in the area for future research," .

Hallan en Perú restos de víctimas de un ritual de sacrificio humano de más de 1.000 años (FOTOS)

Hallan en Perú restos de víctimas de un ritual de sacrificio humano de más de 1.000 años (FOTOS)